I'm sad to part ways with the excellent group of artists I've become so close with over this last week. It's at times seemed to fly by and at other times felt like an eternity; Waiting in the dark for 20 minutes at a time silently or making small talk, 20+ times a day, being mindful of every second passing by, has a way of distorting time. I'll miss the camaraderie of being an extra set of hands for each other as we regularly oscillated between planned lethargy and crisis mode.

Harris advised that I find a way to take advantage of the pulse laser's ability to image something moving, so I decided to put my rocks in water, and disturb the water by lifting and dripping some handfuls of it.

Harris advised that I find a way to take advantage of the pulse laser's ability to image something moving, so I decided to put my rocks in water, and disturb the water by lifting and dripping some handfuls of it.

When it was my turn in the lab we carefully disassembled and transported all the components. The we began setting it up, using the mirror as a standing for the film, as a way to line up our composition, raising and lowering the platform with shims and 2x4s, and then carefully loading in about 3 gallons of water by the coffee mug-full so we wouldn't spill water on any of the optics.

Yesterday had many of those crisis mode moments...

DAY 4

|

| Inside the pulse studio, Jeff Hazelden setting up his model for the shoot before mine. |

The morning started as any other. We gathered, discussed the game plan, and went into the pulse laser lab to set up our installations, one by one. I was the second person out of the five of us to go, and I decided to make another go at my rock pile.

Harris advised that I find a way to take advantage of the pulse laser's ability to image something moving, so I decided to put my rocks in water, and disturb the water by lifting and dripping some handfuls of it.

Harris advised that I find a way to take advantage of the pulse laser's ability to image something moving, so I decided to put my rocks in water, and disturb the water by lifting and dripping some handfuls of it.

I also built a little plank to sandwich between the rocks, projecting forward to hold a second rock pile in front of the larger one behind. This way it would jut forward more in the image and seem to be floating. (and no, I didn't cheat with hot glue. In the spirit of true rock balancing, it's all actually ready to topple at any moment. And often did.) The next step was to fill it with water and practice timing our dripping.

Crisis number one came when it slowly occurred to us that the felt strips we used to mask the edges of the tray were wicking the water out of the tray and gradually flooding the floor of the lab. Lasers and water are not a good thing. On top of that, dripping the water would cause us to potentially get in the way of one of the mirrors.

We decided to simply agitate the water with our hands and then jump out of the frame as quickly as possible, and hope there wasn't too much water on the ground. Frantically, we got it all ready.

3 - 2 - 1 - FOOMP!

20 nanoseconds later it's all done.

We even more frantically (but VERY carefully) cleaned up the flooded floor, and dismantled the installation.

Crisis two came later when someone nearly destroyed another person's hologram by accidentally turning on the yellow lights in the dark room before it had been bleached, which could expose the film and wash out the image. Luckily, somehow, the image wasn't harmed.

After a very stressful morning of close calls, Harris urged us to break for lunch to recompose ourselves.

...That's when we got the alert about the shooter.

An armed home invasion that sent two people to the hospital just off of campus, and the perp was on the loose. The school went on lockdown, so we hunkered down in the darkroom with the doors locked, and used the time to develop some film.

Webster developer heated to 104º (stronger and more caustic than the D19 we used for the continuous wave lasers) for about 4-5 minutes, water rinse, bleach, back to the water for 20 minutes, then squeegee and blow-dry.

We got the notice that the lockdown had been lifted, and my hologram was ready to be viewed.

The setup was a little too high so that from the vantage point of the film you could barely see the water, (which was not nearly as agitated as I 'd hoped) but otherwise it was a really successful shoot.

Each of our holograms got better and better as we went along, and the crises became fewer and farther between.

Eventually, we all finished up, and had some really spectacular masters from which we'd make 4x5" transfers. Sam began setting mine up to be first up for the transfer the next day.

|

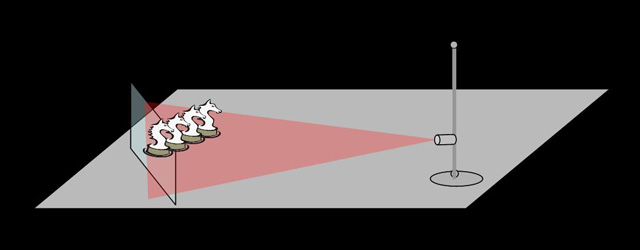

| Lining up the master on the front plate to be projected onto the rear plate with a line source (i'll explain below), where the film would be. |

|

| The projected image (sideways) |

We finished relatively early (that is, not late), and I got back to my host's house just in time for a really great, small party thrown somewhat in my honor. Conversation ranged from holography to foodies to pinball machine repair, to defecation performance art, and I was stunned that not a single one of those topics was any less technical or conceptually rich than any other!

DAY 5

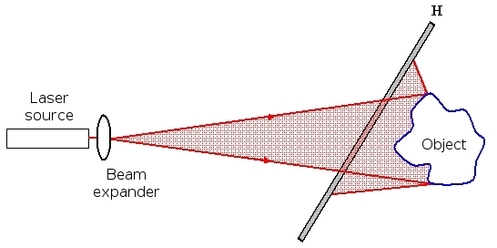

Today we returned for our final day. I was first up for the transfer. The way it works is this: Since every point on the hologram contains all the information for the light scattering off that object and going to that point, you can shine a point source laser through the hologram and end up projecting the entire scene onto the wall. As you move the point around, the vantage point of the projected image moves around accordingly.

Lines and Rainbows:

Instead of shining a point, if you use a cylindrical optic to spread the laser into a line, that line will project the whole image (as seen above) and it will retain all the info for all the vantage points along that line. That gives you a projected image that you can walk past and get the 3D parallax effect. On top of that, the slit aperture of the line source causes white light to spread, creating a rainbow hologram when viewed in white light.

Then, by calculating the focal distance for each 3D portion of the image, you can place the film in the right location to get the transferred image to appear to sit anywhere in space you'd like in relation to the film.

In mine, the rear rock pile sits behind the picture plane (what's called a "virtual" image because it's focal point occupies space that does not physically exist), while the front rock pile appears to just out in front of the picture plane (a "real" object with a focal point in real space in front of the image)

You're then essentially taking a holographic image of a projected holographic image, using that projection as the object beam that mixes with the reference beam to create the interference pattern.

Exposure

Since the optics were already set up the night before (see diagram), all we had to do was fine tune some things, turn off the lights, and load the film between the panes of glass on the rear part of the projection apparatus.

The trick was simply to pick the right spot for the film, since our "window" would be shrinking from 5x14" to 4x5"

Then we wait 30 minutes for it to settle and become stable, tell stories, and figure out our game plans for the exposure - set the timer, lift the card blocking the laser off the table for a minute, uncover the beam entirely and try not to move, breath, or make any sounds, and pray the construction workers upstairs don't decide to start hammering, and watch for 2.5 minutes, then cover the beam again.

Development

Then it's off to the darkroom. It was pretty cool to actually get to the point where we felt we could handle it all by ourselves, without Sam or Harris looking over our shoulder. We all helped each other remember all the steps, and we all had enough experience by this point to be able to coach each other through any minor problems.

And ultimately it turned out fantastically. The only issue was a mysterious streak across the top of the image, but the hologram still developed, meaning the streak couldn't be from a messy object beam. We couldn't find anything in reference beam that could be causing it to overexpose. I thought I might have somehow exposed my film while loading it, but when we saw the same line in everyone else's film too we deduced the it was actually a defect in the roll. Big bummer for the roll, but it was reassuring to me!

Viewing

Since these are transmission holograms (meaning both the object beam and the reference beam collide on the same side of the film) they need to be illuminated from behind (with what's called a "conjugate beam") in order to be viewed. That's why transmission holograms that are hung on walls are actually mounted on mirrors, because it reflects the front mounted lighting back out as if it were coming to the viewer's eyes from behind the film.

Once it was mounted up, we took a look in the white lights, and voila!

I was extremely proud of all of our holograms, and perhaps even more so with everyone's patience through all the waiting, crises, and confusing physics lessons. Tomorrow, after a good night's rest, I suppose I'll take a moment to reflect back and wrap this all up into a nice tidy bow.

But for now, it's time to get some sleep on my last night in Ohio before making the trek back to Jersey in the morning. It's been quite a ride!