Arrival

|

| Windows a la Finch |

It was fantastic to catch up with Brian, the monk-turned-psuedo-apostate-performance-artist whose reverently irreverent assemblages and performative personas toe the line between the sacred and the profane. As we sat down to a burger and some beers, our theological conversations seemed a fitting beginning to this adventure.

I soon settled into my air mattress at my host's quaint one-bedroom apartment. I couldn't help but be a little jealous of its monkish minimalism, and I appreciated that her windows looked like Spencer Finch installations. A much needed retreat from the clutter of this year.

Day 1

It wasn't long before morning came and I was off to campus to meet up with the other artists, a really fantastic group of people:Szofi Valyi-Nagy (Chicago),

Miho Ogai (New York),

Sandra Meigs (Canada),

and Jeffrey Hazelden (Ohio)

Sam Morée, the serious, soft spoken cofounder of the NY Holographic Laboratories and a pioneer of art holography in the 70's, with hair somewhere between Einstein and Warhol was accompanied by Harris Kagan, a tall, good humored, slightly scattered and nervous seeming professor of holography who is one of the team of physicists responsible for the discovery of the Higgs Boson at CERN.

These guys are no joke.

...Well, except when they are, squabbling like an old married couple over the preferred color of a flashlight, or talking over each other to reiterate a point. Entertaining foibles aside, the wealth of knowledge and experience between them is staggering.

After a thorough briefing, we were escorted into the labs for a tour of the equipment and a demonstration of combining laser beams to produce an interference pattern. (This, by the way, is essentially how they used the technology in CERN, Harris explained, noticing simultaneous changes in interference patterns due to gravitational shifts from a cosmic event across a 2 mile long beam length.)

|

| Sam and Harris setting up an interferometer to explain and calibrate the parts - beam splitters, spacial filters, mirrors, beam spreaders, all that good stuff. |

|

| Standing wave interference patterns. Remember the Double slit experiment that helped discover Quantum Mechanics? |

Our First Hologram

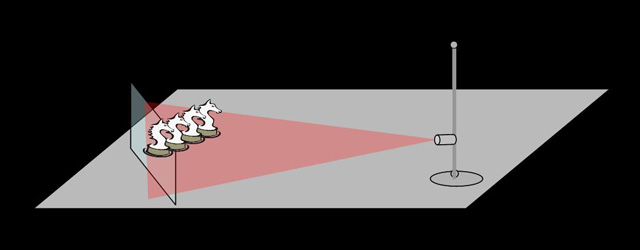

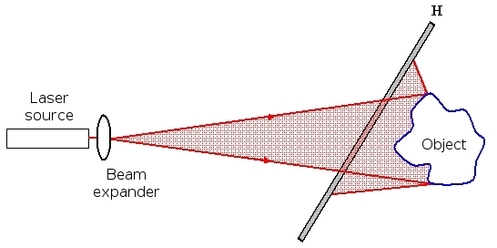

Sam and Harris walked us through an "In-line" transmission Hologram, in which a single beam is used:

After being spread, part of the beam shines directly on the exposure and the other part shines on a lineup of items to be imaged, reflecting off of them onto the exposure. The two parts of the beam (the "reference" beam directly from the laser and the "object" beam reflecting off the objects) mix to create an interference pattern on the exposure that's unique to the way the light hits those specific objects.

You can later shine a laser with the same wavelength on that recorded image, which constructively interferes with the recorded interference pattern and reconstructs for your eye the light as it was seen reflecting off the objects - what our eye sees as the 3D hologram of the object.

STEP 1: Lunch

After a brief max exodus to a Korean restaurant for lunch, Harris led us in setting up the table. He took light readings to plan the location of the exposure within one side of the beam to optimize the beam lengths and ratios (between the object and reference beam's brightnesses), and then we placed our objects in the path of the other side of the beam.

Any hopes of a conceptualism were tossed out the window as we learned why most of the objects we had brought would not image well. We also learned quickly that any answer we provided to what we thought was an intuitive rhetorical question would be the wrong answer, and most of his questions were meant to be intuitive and rhetorical. We've got a long way to go...

Turns out that because of the red light, anything green or less reflective gets imaged as black, anything transparent acts as another optic that potentially distorts the beam, and any movement at all (on a microscopic level) will result in no image.

In this case we started with my pile of rocks, which were quickly deemed uncooperative by their general instability and tendency towards chunky occlusion shadows falling in the way of the other objects.

As everyone else added their objects I scanned the lab's table of nicknacks for a suitable replacement. "Captain Pepper," the porcelain pepper shaker was my stand in, until Harris inadvertently toppled him over, demoting him to the Headless Captain Pepper. With his proud, now disembodied captain head prominently displayed on a pole for all to see, we continued aligning the objects. Well, as he said earlier, "broken things make for much more interesting holograms."

|

| The headless captain and some his companion objects. |

Step 2: Tell stories... seriously though. That's step two.

Once everything's in place, the lights go off and the film goes in the holder (It's just like photographic film, but much denser resolution of silver particles in the emulsion, and sensitive to red neon light).

Then we wait. 20 minutes to let the wood of the frame settle, to make sure that absolutely nothing is moving. With the strength of light we had, it would take a 4 minute exposure.

In those 4 minutes, nothing could move more than 300 nanometers. That's roughly 1/50 the thickness of a human hair! Otherwise, no image! Even breathing or speaking caused enough vibrations to wiggle our test interference pattern, and that's using a $30,000 vibration dampening table!

So we spent those 20 minutes going around and telling stories, waiting for everything to settle. It was a great way to get to know each other, and build artistic community and camaraderie, actually.

|

| Hard to see, but this is the object beam reflecting off the objects, as viewed through the window where the film would go. |

Step 3: Holding Your Breath

Then finally we set a timer and I got to volunteer to hold the black card blocking the laser out of the way for 4 minutes while praying I wouldn't sneeze.

This allowed the laser to shine on the objects and on the light sensitive film. After 4 minutes I replaced the card in front of the laser and on we went.

Step 4: Development

All that was left was to develop the image, darkroom style.

Acid for a few minutes, water rinse for a few minutes, bleach for a few minutes, back to the water, and eventually we had a clear transparency that contained in it all the information of all the light that makes up our visual experience of those objects, from every possible reflected viewing angle, to a microscopic level of detail.

|

| Our completed, developed exposure. |

Tomorrow

We'll be testing out the big kahuna, the Ruby pulse laser, of which there are only a handful of in the world. It's so powerful that it could do our 4 minute exposure in about 1 billionth of a second, completely eliminating any care for object stability. You could throw something and still image it. Our cells don't even change that fast (the human biological rhythm is apparently in the order of a few hundredths of a second).

We'll be imaging ourselves as a holographic group portrait!

We'll also be using a second setup to make "Denisyuk Reflection Holograms," which are another type of in-line hologram using the weaker helium neon laser. The beam passes through the film on its way to the object (with a shallow depth of field) and the reflects off and bounces back to the film. The beams meet in the middle on the film and create the interference pattern.

So the next task is to scramble to find materials to image that are diffusely shiny or bright red/white, with interesting dimensionality, and that fit into a 4x5x1.5 inch box... Reminds me of grad school as we all collude to carpooling to hit up thrift stores and find trinkets and materials to misuse!

|

| The box I have to fill with objects for the next hologram |

Eventually we'll be developing individual projects for the Pulse Laser, creating a laser-viewable master, and then transferring them to holographic prints viewable in white light. Maybe I'll try my rock pile again then. Onward to Day two!

No comments:

Post a Comment